Trophy hunters claim that their money pays for the conservation of endangered animals. But how significant is the money from hunting compared to ecotourism? Why are hunters so obsessed with killing “dangerous” animals – and what does that say about them? And how has hunting affected animals and their cultures? Using the example of African lions, I explain how trophy hunting destroyed a relationship of mutual respect and trust between people and predators, and how we can protect our wildlife and our Earth from the scourge of hunting – legal and otherwise.

“The lions around here don’t harm people. Where lions aren’t hunted, they aren’t dangerous. As for us, we live in peace with them.”

– ≠Toma, senior !Kung hunter, to author Elizabeth Marshall Thomas

Few people in the world can count wild lions among their friends. Then again, most people aren’t Dr. Andrew Loveridge, who has been part of Oxford University’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) since 1994, and has published over 60 groundbreaking studies on Africa’s carnivores, including more than 20 peer-reviewed papers on lions alone! For a wildlife researcher, that means living amongst lethal predators that that most of us fear – watching them prowl, sleep, hunt, fight and raise their cubs.

To see an adult lion is to behold a warrior – someone who has survived an unforgiving childhood, adolescent exile, and nomadic wanderings of an uncertain youth. He has mastered the fear of pain and death to battle stronger, more experienced lions for supremacy over a pride, who safeguards a vast kingdom for his cubs, and who his family rely on to bring down powerful prey such as the fearsome African buffalo.

He Was A Lion And He Knew It

So it’s an exciting time for researchers when a new lion arrives on the scene. In 2008, two six year old lions – wandering brothers – showed up in the southern part of Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park, near a waterhole called Magisihole Pan. Researchers from WildCRU named the brothers Cecil and Leander, after two prominent figures in Zimbabwe’s history. Magisihole Pan happened to be part of the territory of an established pride, led by a powerful lion called Mpofu. For about a year, Cecil and Leander slinked about warily, hunting on the sly, eating carrion, and avoiding confrontations while observing their rivals. And then they staked it all on a direct battle, challenging Mpofu for supremacy. The bloody fight killed Leander, and both Cecil and Mpofu were seriously wounded. Mpofu’s injuries, which included multiple fractures, were so grievous that park rangers had to put him down.

For young Cecil, it was a stunning coup. He recovered from his injuries, and took the reins of his new kingdom. Every lion, like every human, has a unique personality. Cecil “was the most confident lion on the block — confident, but not aggressive … He was not really playful — more regal. He was a lion and he knew it, and everyone else be damned — he was the biggest cat on the block, and he didn’t have to be playful,” says Zimbabwean researcher Brent Stapelkamp, who has been with WildCRU since 2006. Cecil’s personality won him a lifelong friend, another massive lion called Jericho. In fact, after Cecil was murdered, it was Jericho who raised his cubs like his own. But that comes later.

Researchers like Stapelkamp and Dr. Loveridge can tell one lion from another. It isn’t surprising that lions can also recognize people they see regularly. One time, Cecil saw an odd sight – an employee at Linkwasha Camp awkwardly carrying a heavy load of laundry. Anyone with cats can guess what happened next. Whether on impulse or out of curiosity or as a prank, Cecil ran toward him. Seeing the lion approaching, he paled and collapsed to the ground. As he saw that, Cecil stopped instantly … And he let him go.

Going by the tall tales that hunters tell, Cecil should have killed this man instantly. “It was either me or that lion – kill or be killed.” And yet, each year millions of tourists tour protected reserves like Hwange in open-top 4x4s, sometimes coming within mere feet of prides of lions, and yet the lions do nothing to harm the tourists (nearly all of the rare incidents of lions attacking tourists have taken place in “safari parks” with captive lions.

Ultimately, it wasn’t Cecil or any other lion that betrayed the trust of humans. It was people – specifically, trophy hunters – who betrayed the trust of lions.

Trophy Hunting Is Messed Up

There isn’t much to be said about the killing of Cecil that hasn’t been said already. But what also surprised me was the clumsy manner in which Walter Palmer had killed him. Why, for instance, was Cecil allowed to suffer for hours? Why was he, specifically, drawn out of the protected area by bait? And why didn’t Walter Palmer bring back Cecil’s skull, as trophy hunters normally would, if he believed he had killed him legally?

As I researched the culture of trophy hunting, investigated lobbying groups like Safari Club and read Dr. Loveridge’s account from his upcoming memoir, Lion Hearted: The Life and Death of Cecil and the Future of Africa’s Iconic Cats, I began to put the pieces of this puzzle together …

The long and short of it is like most trophy hunters, Walter Palmer wasn’t merely interested in bagging a lion. He wanted a record. This is very important to understand. You see, trophy hunters are oddly obsessed with making record kills – specifically, getting into three obscure record books that few outside the hunting community have heard of. These records are: Safari Club’s SCI Record Book of Big Game Animals, the Boone and Crockett Club, and the Pope and Young Club. Walter Palmer, for instance, had bow-hunted all but one animal on Pope and Young’s list, including the polar bear.

Palmer let Cecil suffer in agony for hours because he wanted him to die from an arrow wound. Killing a lion as big as Cecil would have been a new bow-hunting record. And if bagging a ‘record’ trophy and winning the admiration of his hunting peers meant that Cecil bled and suffered for hours, then so be it! After he was exposed, Palmer stated, “I deeply regret that my pursuit of an activity I love and practice responsibly and legally resulted in the taking of this lion.” This creates the impression that Palmer was conned into unwittingly killing a lion illegally. However – and this is important – evidence collected by Dr. Loveridge shows that Cecil’s carcass was skinned, loaded on a vehicle, and transported elsewhere. This is called “quota swapping” – disposing a carcass elsewhere so that the limited hunting quotas for an area aren’t used up. He also didn’t collect Cecil’s skull, as a trophy hunter would have. He didn’t care about the skull. All he wanted was an entry into those stupid record books.

Every Trophy Hunt Is A Canned Hunt

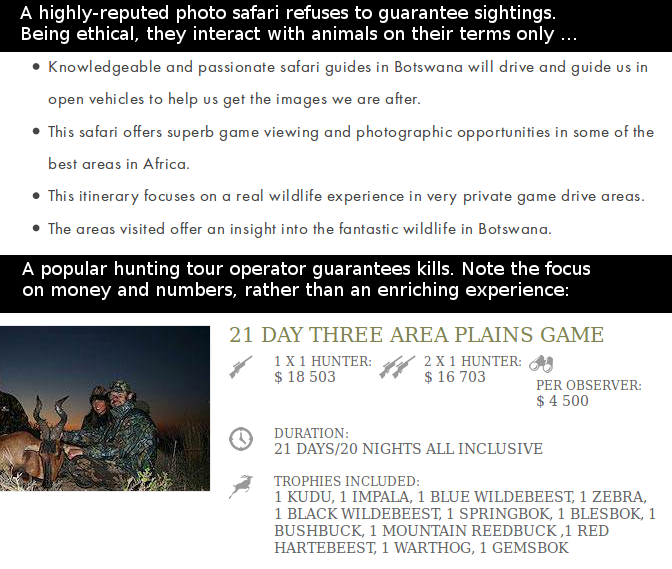

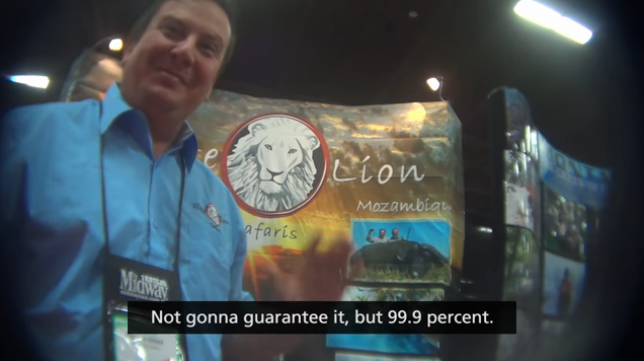

This obsession with hunting records such as Safari Club’s is what has created the bizarre, messed-up culture of trophy hunting. It’s the reason why irrespective of whether lions are wild or captive-bred, every trophy hunt is rigged. On a photo safari, you may or may not see the animal you’re interested in. No safari operator will ever guarantee that you’ll see a lion, leopard or tusker on your drive (although most tourists do, over and over). But hunting companies not only guarantee that their clients will kill the species they want, but can even guarantee a specific size, color and other ‘bonus’ trophy animals as a package.

Why? Because if the hunter doesn’t bag the kill, the operator doesn’t get paid. Thanks to hunters’ obsession with record books and the hunting company’s ‘no kill no pay’ guarantee, every trophy hunt is a canned hunt.

Trophy hunters pay upward of $30,000 to kill a lion – of which less than $900 goes to local communities. Many of these hunts are purchased at auctions … the death warrants of these lions are signed months in advance, on a different continent. The same is true for elephants, giraffes, antelope, zebras, crocodiles, and all other victims of the trophy hunting business.

In the bush, trophy hunters are guarded by ‘professional hunters’ (“PH” in hunting lingo). Their job is to kill the animal if it poses any danger to their client. Faced with teams of trackers, drivers, trophy hunters and their bodyguards equipped with radio sets, vehicles and high-powered weapons, what chance does a lion have?

But What About All The Money That Hunters Spend?

After Botswana outlawed lion hunting, its lion population stabilized and then increased, contrary to the (self-serving) predictions of the trophy hunting lobby.

In 1968, shortly after outlawing all hunting, India had only 178 lions. By 2015, their numbers had increased to 523, and are estimated to be over 650 today – a 365% increase in just five decades.

But wait … wouldn’t outlawing trophy hunting dry up all the funds for conservation? What about all that money needed for patrolling lands, fighting poachers and stopping all those “savage” natives from destroying it all?

Studies by the government of Botswana, the IFAW and numerous other organizations reveal that barely 3% of trophy hunting fees actually trickle down to local communities. A typical hunting preserve employs no more than 10 to 15 local people. According to the IUCN, trophy hunting has created only 15,000 jobs in all of Africa – that’s less than 0.01% of the population of just 6 of Africa’s top safari destinations!

The hunting lobby loves to brag that they contribute $200 million each year to Africa’s economy. Aside from the fact that Africa comprises 54 countries (making this paltry contribution even more laughable), that statistic is based on a 2011 report by Larry Rudolph and Joe Hosmer. Larry is the President of Safari Club International, and Joe is the President of the Safari Club International Foundation. SCI’s motto is ‘First for Hunters’. Talk about conflict of interest! And what’s more, $100 million of this magical $200 million figure comes from an unpublished “study” by … (you won’t be surprised) … the Professional Hunters Association of South Africa!

“We’re more closely allied with the photographic operators than the hunters. They are finishing off the wildlife before we’ve had a chance to realize a profit from it … We’re supposed to get 5 percent: we don’t see even that.”

– Tanzanian village officer, quoted in the Oxford University study Wildlife Is Our Oil: Conservation, Livelihoods and NGOs by H.T. Sachedina (2008)

Contrast this ridiculous “$200 million for all of Africa” with the money contributed by ecotourists – travelers from all over the world (including domestic tourists) who pay smaller fees to spend time with wild animals and photograph them … In Kenya (that’s just one country in Africa), which outlawed hunting in 1973, ecotourism contributes around 10% to their GDP, and gave $6.21 BILLION to the people of Kenya in 2016 alone!

Trophy hunters quote their own “studies” to claim that they give $200 million annually to the entire continent of Africa. By contrast, ecotourists earn over $6,200 million each year for Kenya alone!

Overall, ecotourism – wherein people visit protected areas in Africa just to watch and photograph the wildlife – contributes tens of billions – that’s billions with a B – to Africa’s economy. Wildlife preserves that cater to photo tourists, rather than hunters, typically hire 150 to 200 people, and offer livelihoods to hundreds more in local communities. In Botswana, ecotourism employs 40% of the working population! Unlike trophy hunters, ecotourists are far more likely to live among local communities, purchase native art and use native guides.

Bryan Orford, a professional guide at Hwange, calculates that tourists from just one of many lodges in the area collectively pay $9,800 per day to watch and photograph wildlife. A mere 5 days at a single safari lodge generates more revenue than the $45,000 fee that a trophy hunter would pay to kill a lion like Cecil.

Award-winning wildlife filmmaker Dereck Joubert wrote for Africa Geographic:

“We once did a survey in Savuti in Botswana and calculated the value of a male lion dead (as a trophy) versus its value as an eco-tourism asset. It is complicated but its value dead was US$15,000 at that time whereas its value alive was around US$2,000,000 …

“A photographed lion yawns at the dawn repeatedly for photographs for over 10 years, attracting fees and lodging costs and also, importantly, distributing value down the chain to airlines, wages, curios, communities and food purchases (none of which were actually included in the US$2M calculation). However, one bullet ends those yawns in the sunrise forever for that lion.”

He further explained in National Geographic:

“One former hunting area called the Selinda Reserve was converted to only photographic tourism. The increase in wildlife has been spectacular; the increase in revenue to government and its people is something like 1,300 percent. Employed people have the benefit of real skills transfer and training. The old hunting companies hired minimally; now instead of 10 or 12 jobs in these areas there are 180 people employed full time just in this one reserve.”

But trophy hunting doesn’t merely worsen the economic divide in Africa. It is also …

A Problem Of Race And Class

Across much of the world, and especially in Africa, life has been shaped by colonialism, racial segregation, slavery and economic exclusion. For many people, these are not historic artifacts, but social evils that victimized their parents and grandparents, and continue to affect them today. And the same culture of entitlement that encouraged these practices, lives on in the culture of trophy hunting.

A recent Newsweek report reveals that trophy hunters are “mostly white Americans, although there are plenty of moneyed Europeans and Russians. They are almost always men and, curiously, often have medical degrees.” Racism toward Africans is apparent in condescending remarks by trophy hunters about feeding natives. High school cheerleader Kendall Jones, all of 19 years of age, who posed with her boot on the corpse of a white lion, says in an interview, “I had hunted an elephant. That one hunt fed more than 100 families. If more people hunted and gave away meat like I did, hundreds or even thousands of people in Africa could be fed.”

For perspective: The license to hunt an elephant costs around $20,000. For a lion, around $30,000. Including air fares, luxury travel, money spent on killing more animals, etc., a 14-day murder spree in Africa can cost upward of $70,000 per person. In a part of the world where 80% of natives are subsistence farmers, all that money could have built wells, irrigation canals and storage facilities all over the province. Or it could have electrified dozens of villages with solar panels, which in turn would have kept their children in school (children who work farms cannot study after dark), increased their incomes by letting them use cellphones to find the best markets for their produce, and transformed their lives for generations to come! But I suppose that doesn’t feel as gratifying as shooting a 70 year old elephant, chopping off his tail, and watching a few dozen impoverished villagers squabble over his lead-poisoned carcass.

“There is a growing sense with respect to the poachers that white people get away with murder. Here, you see the seeds of the racial disconnect … [It’s] priming a massive, explosive situation, which, of course, will go way beyond wild animals … And if you went to the funeral of a poacher, you would see this person is revered, and it’s not shameful.”

– Martin Bornman, African Conservation Experience

Trophy hunting has always been fueled by a craven desire to flaunt one’s wealth and social status. Perhaps the reason why so many bored, wealthy and insecure people enjoy trophy hunting is because, aside from the obvious thrill of having power over the life of another, they can get away with something that would destroy a poor person’s life. Comedian Jim Jefferies does a brilliant job of explaining this (starting at 5:04) …

No longer restricted to bas reliefs, the bloody exploits of trophy hunters are shared on Facebook pages, displayed in trophy rooms and recorded as ‘Lifetime Achievement awards’, ‘Hall of Fame Award’, ‘Diana Award’, ‘Young Hunter Award’, ‘Inner Circle’ and other meaningless recognitions. The impulse for trophy hunting is as primitive as it’s always been, driven by an acute and perverse need for social validation.

What has changed – thanks to social media – is that for the first time in human history, people who are too ethical to pay $50,000 to kill a cat now have a voice. To see how most people despise trophy hunters, just visit the comments section of any Facebook album or news article about a trophy hunter.

After all, we have an innate sense of fairness, of right and wrong. Most of us will never see these golden felines in the flesh, and yet the very idea of this supreme predator – its mane like a golden stormcloud, roar like rumbling thunder, eyes like amber and claws that can shred steel – inspires fear and admiration in equal measure.

Why Lions Mean So Much To Us

Lions hold a special place in our hearts and our culture. Lions feature on the flags or emblems of Great Britain, Scotland, Wales, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Czech Republic, Estonia, Montenegro, Armenia, Bulgaria, Georgia, Sri Lanka, Singapore, Cambodia, Philippines … and none of these countries have lions!

Clearly, lions affect us at a raw, primal level. Spotted hyenas are more effective predators than lions, but Disney will never make a Hyena Queen. Recent scientific studies explain why lions mean so much to us …

Lions might be why we like tall buildings and treehouses

Richard Coss and Michael Moore, psychologists at the University of California, Davis, wanted to understand whether our attitudes toward predators are learned or instinctive. They created a virtual model of an African savanna, with an acacia tree, a kopje (rock hill), and rock crevices. They then showed this model to groups of preschool children, and conducted 3 experiments. In the first, the children were shown a lion in the savanna and asked to choose the safest spot. With no prior experience with lions, acacia trees or boulders, 5 out of 6 children wanted to climb the tree or hide in the crevice. With no knowledge of predatory behavior, these preschoolers instinctively knew that the kopjes were unsafe.

In the second experiment, they showed preschoolers from Israel, Japan and the US silhouettes of trees they’d never seen before – an Australian pine, a fever tree, and acacias. They were then asked to choose the prettiest tree, and the one that they’d climb for refuge. While most of the children elected the Australian pine as the prettiest tree, they overwhelmingly chose the high-canopied acacias for protection from carnivores. Finally, another group of preschoolers was asked to choose the best location in the canopy of each tree for protection, and most of them chose the edge of the crown, which would be the safest place for protection from heavily-built predators like lions.

What’s even more fascinating is that significantly more girls than boys chose to climb trees for refuge, and chose the highest, thinnest branches. On average, girls are more lightly built than boys. Somehow, with no experience with climbing trees, no knowledge of the African landscape, and only a rudimentary understanding of the dangers that lions can pose, most of the children from varied backgrounds instinctively made correct, life-saving decisions.

This instinctive preference for the safety of trees and rock crannies, which kept our early ancestors alive as their woodland homes transformed into endless savannah, still offer us much comfort today. It’s part of the reason why we erect stone castles, build igloos, pray in churches with high steeples or temples on mountain-tops, pay a premium for penthouse apartments, love treehouses, and fantasize about hobbit holes.

Lions, Jaws and Jurassic Park

At the UCLA, anthropologist Clark Barrett asked a different question: can humans instinctively understand the intentions of predator and prey species? To discover this, he used two groups of 3 to 5 year olds. One group was preschoolers from Germany, and the other was children of the Shuar tribe, which lives in Ecuador’s Amazon rainforest. He then showed them two toys – a lion and a zebra. He then asked each child, “What does the lion want to do when he sees the zebra?”

The Shuars live in the Amazon rainforest, and Germany, of course, is an industrialized country. The life experiences of these children couldn’t have been more different, and neither group had any experience with lions. And yet, their responses were remarkably similar. Among the 3-year olds, all Shuars and 3 out of 4 German kids figured out that the lion wants to chase the zebra. All 4 and 5 year olds answered this question correctly.

Barrett then asked each child, “What will happen if the lion catches the zebra?” For the German children, 67% of the 3-year olds replied, “The lion will hurt / kill / eat the zebra.” Older German children and all Shuar children also assessed the situation correctly.

Barrett calls this the “Jurassic Park syndrome“. His experiments indicate that we have an instinctive understanding of what animals can be dangerous, based merely on how they look. It’s why we’re fascinated by Great White sharks, who have large teeth, but not whale sharks, who are twice as big, but harmless. Clearly, Steven Spielberg knew what he was doing – his velociraptors in Jurassic Park were four times larger than actual velociraptors, with bigger skulls and jaws.

What this study reveals is that hunters’ high opinion of their courage and prowess is not based on any actual risk in hunting, merely the perception of danger. Simply put, lions look and sound dangerous to our primate brains. After all, black footed ferrets are endangered in America, but you don’t see Safari Club trying to auction ferret hunts for $50,000 each!

For all their verbal gymnastics, trophy hunters are seeking a hormonal high that ends in the deaths of animals that do more for our Earth than they ever will. To put this into perspective, gamers worldwide get their adrenaline fix from Star Wars: Battlefront and Overwatch (which require more skill than trophy hunting) – and all they kill is time.

The Myth of Man the Hunter

Over many decades, books and movies have portrayed early humans as tough, fearless cavemen who hunted mammoths with stone spears and wore the skins of cave lions. The idea is that even primitive humans were formidable hunters who commanded fear in once-mighty predators.

This myth remains persistent even today. The entire ‘paleo diet’ fad views agriculture as the ‘beginning of the end’ of sorts, when humans gave up their glorious hunter-gatherer ways and effectively abandoned their rightful place at the ‘top of the food chain’.

This myth is far removed from reality. But popular culture interferes with good science more often than science shapes our culture for the better. There is ample evidence that for most of our evolutionary history, we have been a prey species, not a predator. This is a bitter pill to swallow. When anthropologist Raymond Dart discovered the first fossils of Australopithecus in 1924, he noted the holes in their skulls and marks on their bones, and concluded that our ancestors not only killed and ate animals, but also killed each other using bones as weapons. This came to be known as the Killer Ape hypothesis.

For most of our evolutionary history, we have been a prey species, not a predator. This is a bitter pill to swallow.

Author and playwright Robert Ardrey popularized this view in the 1960s. He wrote, “Man is a predator whose natural instinct is to kill with a weapon.” He reasoned that the natural (and therefore, justified) drive that apparently compelled our ancestors to hunt mammoths and cave lions now manifested themselves in war and genocide – the Holocaust of the 1930s, atomic bombings and tests in the 1940s, the Korean war in the 1950s, the Vietnam war in the 1960s and so on. In his book The Hunting Hypothesis he writes, “If among all the members of our primate family the human being is unique, even in our noblest aspirations, it is because we alone through untold millions of years were continuously dependent on killing to survive.”

“We were born of risen apes, not fallen angels, and the apes were armed killers besides. And so what shall we wonder at? Our murders and massacres and missiles, and our irreconcilable regiments? Or our treaties whatever they may be worth; our symphonies however seldom they may be played; our peaceful acres, however frequently they may be converted to battlefields; our dreams however rarely they may be accomplished. The miracle of man is not how far he has sunk but how magnificently he has risen.”

– Robert Ardrey, African Genesis: A Personal Investigation into the Animal Origins and Nature of Man (1961)

Perhaps it was expedient to blame war crimes on “evolution”. But Dart’s conjectures and Ardrey’s propaganda were based on a flawed understanding of our past. The injuries on the australopithecines were not the result of conflict, but predation. Simply put, our evolutionary ancestors were not killing each other – they were being killed – and eaten – by true carnivores, including felines, hyenas, and even eagles.

This was shown in the 1970s by paleontologist Charles K. Brain (finally, someone with a Brain), who showed that the holes in their skulls are a perfect fit for the canines of saber toothed cats. The bones were not weapons, but what remained of ape corpses after their predators were done with them. And what’s more, these fossils show that 6% to 10% of all early humans were hunted – a percentage similar to that for present-day savanna antelope and ground-dwelling monkeys.

Despite what science shows, the Killer Ape myth persists in popular imagination and scientific bias. Robert Sussman, anthropologist at Washington University, St. Louis and co-author of Man the Hunted: Primates, Predators and Human Evolution thinks that this belief is rooted in Judeo-Christian ethos. That isn’t far-fetched, inasmuch as Biblical texts declare that man has absolute right over “everything that lives and moves about”, and celebrates the “fear and dread” that “every beast of the earth” feels – or must be made to feel – at the sight of Man, created in the image of God himself.

Significantly, the Judeo-Christian ideology is also highly patriarchal. Is it any surprise that mainstream human culture clings to the idea of men bravely stepping out into the untamed wilderness, putting saber-toothed tigers to flight, spearing cave bears, hunting woolly mammoths, and returning back to their women (who knew their place and stayed in the cave-kitchen) with fresh meat, fur and ivory?

Is it also surprising that this ideology, which sanctioned the extinction or near-extermination of whales, beavers, passenger pigeons, quaggas, tigers, Tasmanian tigers and many other species in the name of commerce or sport, was also used to justify wanton crimes such as slavery, colonialism, and the genocide of native Americans and Aborigines?

And yet, a few conscientious, committed people can reform practices and institutions that have changed little for centuries or millennia. In his 2015 encyclical (letter to all bishops) titled Laudato Si’, Pope Francis writes:

“33. It is not enough, however, to think of different species merely as potential “resources” to be exploited, while overlooking the fact that they have value in themselves. Each year sees the disappearance of thousands of plant and animal species … The great majority become extinct for reasons related to human activity … We have no such right.

“36. Caring for ecosystems demands far-sightedness … Where certain species are destroyed or seriously harmed, the values involved are incalculable. We can be silent witnesses to terrible injustices if we think that we can obtain significant benefits by making the rest of humanity, present and future, pay the extremely high costs of environmental deterioration.”

Man the Hunter-Gatherer, emphasis on ‘Gatherer’

Studies of present-day hunter-gatherer societies (which still use Neolithic tools) reveal a different picture. In hunter-gatherer societies across the world, between 60% to 90% of the food is gathered, not hunted, and most food collection is done by women. Most of the tools used, from digging implements to woven baskets, are also designed by women. That isn’t to say that the men are lazy, or that hunting is irrelevant to these societies. But hunting is time-consuming, risky, and has unpredictable outcomes. This is why most subsistence hunters kill small animals – spider monkeys in the Amazon, hares in the Kalahari and fish in the Arctic.

These studies are corroborated by numerous first-hand accounts. Few have researched hunter-gatherers as extensively as anthropologist and author Jared Diamond. In his book The Third Chimpanzee he writes …

“The mystique of Man the Hunter is now so rooted in us that it is hard to abandon our belief in its long-standing importance. Today, shooting a big animal is regarded as an ultimate expression of macho masculinity. Trapped in this mystique, male anthropologists like to stress the key role of big-game hunting in human evolution. Supposedly, big-game hunting was what induced protohuman males to cooperate with each other, develop language and big brains, join into bands, and share food. Even women were supposedly molded by men’s big-game hunting … “

He states that it isn’t just Western men who are fascinated by hunting. Describing his time with hunter-gatherers in New Guinea, he explains, “To listen to my New Guinea friends, you would think that they eat fresh kangaroo for dinner every night and do little each day except hunt. In fact, when pressed for details, most New Guinea hunters admit that they have bagged only a few kangaroos in their whole life.”

Diamond goes on to narrate a hunt that he went on with “a dozen men, armed with bows and arrows”. As the hunt progressed, the men found something – “there was suddenly much excited shouting … some spanned their bows … then I heard triumphant shrieks”. They had caught “two baby wrens, not quite able to fly”, and then proceeded to catch “a few frogs and many mushrooms”.

He concludes:

“Studies of modern hunter-gathers with far more effective weapons than early Homo sapiens show that most of a family’s calories come from plant food gathered by women. Men catch rabbits and other small game never mentioned in the heroic campfire stories … For most of our history we were not mighty hunters but skilled chimps, using stone tools to acquire and prepare plant food and small animals. Occasionally, men did bag a large animal, and then retold the story of that rare event incessantly.“

John Vaillant, author of The Tiger: A True Story of Vengeance and Survival, suggests that ironically, gathering, not hunting, may explain the dynamics of our relationship with lions and other big cats. He describes how in 1969, when obsession with the Hunting Hypothesis was at its peak, author George Schaller and anthropologist Gordon Lowther took a series of walks in Serengeti National Park to study predator-prey relationships. As they followed one lion for three weeks straight, they made a surprising discovery. In those three weeks, Schaller writes, “it killed nothing but ate seven times, either by scavenging or by joining other lions on their kill.”

If a lion could sustain himself by scavenging, they wondered if early humans could have gotten all the meat they needed by scavenging instead of hunting. In calving season, they found eighty pounds of meat in just two hours, in the form of calves and carcasses. In their next study, they focused solely on carrion, and in the course of one week, found “nearly a thousand pounds of edible animal parts”. Considering that there were only two of them, not a tribe that could spread our over a large area, they concluded, “a carnivorous hominid group could have survived by a combination of scavenging and killing sick (and young) animals.”

Of course, carrion is rarely lying unattended on the open savannah – vultures, hyenas and prides of lions will readily eat any scrap of meat or bone within sight. What chance could a troop of ground-dwelling apes, without fangs or claws, stand against such formidable predators? Yet, as Schaller and Lowther noted, “All of the seven lion groups we encountered while we were on foot fled when we were at distances of 80 to 300 meters.” Incredibly, faced with two confident human beings, entire prides of lions abandoned their kills and moved off.

This might seem far-fetched, but from a lion’s perspective, it’s a sound survival strategy. To most predators, a long-term injury is as good as death by starvation. Confronted by a clan of 20, 30 or 50 hominids – screeching, tossing rocks and waving sticks – why would lions risk injury when they can find easy prey elsewhere, or even chase a hapless jackal or cheetah off a kill?

For their series Human Planet, the BBC filmed three Kenyan Ndorobo hunter-gatherers intimidating a pride of 15 lions into abandoning their wildebeest kill, then leaving off with a share before the lions rallied and charged. Watching this, the narrative of spear-wielding hunters hunting large, dangerous animals for food seems downright ridiculous …

A lot of the self-congratulatory bravado in the hunting community stems from the danger supposedly posed by ‘big game’ like lions. And even though most people are opposed to hunting, there’s a widely-held belief that given a chance, a lion will instantly kill and eat a human being. If more people knew of the extent that lions will go to avoid confrontation and be left in peace, trophy hunters would be despised even more than they already are.

A Timeless Truce

As we discard egotistical notions of our invincibility and examine the evidence, from prehistoric sources such as fossils and cave paintings, as well as present-day hunter-gatherer societies, a new picture emerges – not Man the Hunter, but Man the Peacemaker. We did not conquer the world by defeating blood-thirsty carnivores that wanted to exterminate us. We thrived because our ancestors negotiated truces or formed alliances with the non-human animals that shared their lands.

In fact, our ancestors often saw these formidable carnivores and powerful herbivores as their kin and their guides. They respected them; oftentimes they revered them. They painted them in their cave dwellings, imitated them in their costumes and dances, and wove them into their songs and stories that they passed down to their children, much as they taught them how to build fires and make tools.

What emerged was not a ferocious bipedal superpredator, but a highly intelligent and emotionally aware species of ape who relied on a nuanced understanding of his fellow animals to thrive in his homeland. Prehistoric humans learned the many languages of animals, read the scripts written in the land and the sky, and shared these lessons with their kin, forming cultures that helped them adapt to life on savannahs, in rainforests, on archipelagos, in the mountains and in fertile river valleys where they first domesticated the plants and animals that formed the bedrock of human civilization.

We thrived because our ancestors negotiated truces with other species.

Until as recently as the late 20th century, one could experience this human-animal culture in the baked wilderness of the Kalahari. Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, author of numerous books on ‘primitive’ cultures, lived for a while with the !Kung Bushmen in the central Kalahari. When her family arrived there in 1950, the !Kung were the only other humans around, living in that vast wilderness as they had for tens of thousands of years, with a Paleolithic culture and technology. They took these new immigrants under their wing and taught them how to survive in that parched desert – and one of the lessons was how to behave around lions.

Thomas learned that if they crossed paths with a pride of lions, they must “walk purposefully away at an oblique angle without exciting the lion or stimulating a chase.” And this was also what lions taught their cubs. If the !Kung and lions crossed paths, each party would walk nonchalantly, pretending to be interested in something else. That way, neither party lost face or precipitated a confrontation.

With few plants around to provide year-long sustenance, the !Kung were dependent on hunting with poisoned arrows for their survival. This poison took time to act, so they were compelled to track their victims for many miles after they were shot. Every now and then, they’d come upon their dead victim, only to find that lions had gotten to it first. Rather than abandoning the hunt, or shooting the lions, they would approach them calmly. As they did so, they would speak to the lions firmly, telling them that the kill wasn’t theirs and that they needed to hunt something else. If that didn’t work, they’d pick up some dirt and toss it in their direction, repeating their requests firmly. And that was all that it took for the lions to walk off and surrender the quarry to the Bushmen.

Rather than shooting the lions, the !Kung would approach them calmly, telling them firmly that the kill wasn’t theirs. And the lions would walk away.

The Web of Life in the Kalahari wilderness was sustained by a Web of Culture. And the cultures that made up this Web had been passed on for countless generations of lions and humans. Just as lions taught their cubs not to harm humans, the Bushmen in turn taught their children to respect lions and give them their space. Those prides and tribes didn’t merely cohabitate a landscape – they shared a bond of trust and mutual respect that had stood the test of time.

This fragile trust was shattered as more settlers and big game hunters began moving into the area. To them, these lions were easy ‘game’ who showed no hostility and made no attempt to retaliate. By 1965, the !Kung were forcibly evicted from their homeland for establishing Etosha National Park. By the 1980s, when Thomas visited the area again, something unimaginable happened – the once-peaceful lions charged at her car. The silken thread that had bound man and lion for millennia in courteous coexistence was now broken. The younger lions, with no adults to instruct them in human-lion etiquette, saw humans as a threat and cars as potential prey. It took many more years for Etosha’s lions to get habituated to tourist vehicles, but the culture of the ‘oblique walk’ is now gone forever.

A Timeline

Hominids have coexisted with lions for 2.8 million years. Anatomically modern human beings (Homo sapiens) branched out as a distinct species in the Mid Paleolithic – around 200,000 years ago. Evidence shows that our ancestors only began hunting regularly around 60,000 years ago.

For most of these 60,000 years, conflict with lions was virtually non-existent. Agriculture started in fertile river valleys around 12,000 years ago, and records from ancient Egypt indicate that the first lion hunts for sport only occurred around 5,000 years ago. Although Barbary lions were gone from Europe and parts of North Africa by the 1st century AD, there remained widespread across Africa and Asia.

But it was only in the past 250 years, with the spread of colonialism, that trophy hunting of lions began in earnest. Asiatic lions were quickly exterminated across most of western and southern Asia, until only 12 to 20 clung on to existence in Saurashtra, western India, where they received protection for decades until post-colonial India outlawed all hunting in 1973. The genocide of Africa’s lions began in earnest in the mid-1880s, when the continent was carved up amongst colonial powers – see ‘Scramble for Africa’.

In the 2.8 million years that we have been on Earth, we were living as gatherers or scavengers for 97.9% of our history. In our evolutionary history as ground-dwelling apes, we’ve only been farming for 0.43% of our existence. Until 5,000 years ago – or for 99.998% of our shared existence, lions have never had to fear persecution by human beings.

In just 0.002% of our shared history, we’ve killed 98% of all lions.

And for lions, who have no instinctive fear of human beings and who had no reason to suspect that a trophy hunters would treat them any differently than native hunters (who lived at peace with them), the age of trophy hunting was to lions as the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius was to Pompeii.

It’s estimated with much certainty that even as recently as the 1880s (prior to colonization), there were more than 1,000,000 wild lions in sub-Saharan Africa. Just seven decades later, this number had halved to 500,000 by 1950. By 1975, only 200,000 lions remained in Africa. While Africa was wronged in every conceivable way during the colonial era, the blame for this particular catastrophe lies squarely with trophy hunting. In just the past 100 years, 90% of Africa’s lions have been lost – and one way or another, trophy hunting is to blame.

Why Trophy Hunting is Genocide

Lions are social animals, and dominant male lions – who are also the biggest and have the most luxuriant manes – protect the younger males and cubs on their territories from rivals. Male lions also bring down large prey like buffalo, which are a crucial part of their diet. The death of a dominant male can cause much bloodshed and chaos in leonine society for years. With each lion that trophy hunters kill, they effectively destroy the pride and cause dozens of deaths over many months.

“You kill one male and from that may flow the deaths and disruption of many others. One dead male is not one dead male, it is a cascade of consequences.”

– David Macdonald, director of WildCRU

Take for instance, Cecil, the lion whose cold-blooded murder by dentist Walter Palmer sparked (unexpected) worldwide condemnation. In 2016, barely a few months after he was killed, experts stated that he had at least 28 descendants – 13 cubs and 15 grandcubs. Thankfully, his best friend Jericho protected Cecil’s bloodline from rival lions. It could not have been easy for a single lion to protect dozens of cubs (Cecil’s and his own) and several lionesses from almost certain death.

Most lion cubs are not so lucky. In almost all cases, the killing of a ‘trophy male’ dooms all the cubs in his pride. Even the adolescent males are killed by invading lions taking over the undefended pride.

Since trophy hunters kill the biggest lions with the best genes – the very lions who have large families, a single bullet can kill 20 to 30 lions … the “trophy” lion, dozens of cubs, and his male friends who will probably die fighting invading nomads.

But there’s no guarantee that these nomads, who have not ‘earned their place’ and may not be experienced fighters, will successfully defend their territories from other males. They may be killed in a few months, leading to another cycle of cub killing. And another. And then another …

Meanwhile, with these newer males busy defending their prides and suffering injuries or dying, lionesses find it harder to hunt enough prey. Without the support of males, they may suffer serious injuries hunting prey like buffalo. And with many young, vulnerable cubs, fewer lionesses to go on hunts and constant raiding by other lions, infant mortality spikes.

In effect, the murder of a single ‘trophy’ lion can kill many dozens of lions over the next few months. In fact, it can lead to a total breakdown of the leonine society in that area. In this chaotic society, with less instruction from experienced adults, younger lions can get into serious trouble with the native people – killing livestock or injuring people – only to be labeled as ‘problem lions’ and be shot, speared, poisoned or snared.

When trophy hunters claim that the steep declines in lion numbers are from poaching, not ‘legal’ hunting, they are bullshitting you. If a lion pride is ruined by the untimely death of its patriarch, does it really matter if the bullet was legally sanctioned or not? Arguably, since trophy hunters kill the biggest males with the best genes, and natives usually kill younger, nomadic males, trophy hunters do more damage than poachers, even if they shoot fewer animals.

Hunters Cannot Replace Predators

Since the relatively-recent environmental movement, there has been increasing social pressure for the end of trophy hunting. And so the trophy hunting industry has had to tweak its narrative of lies again. While Colonial-era hunters associated the massacre of African wildlife with “bringing civilization to the savages”, and mid-20th century hunters spoke glowingly of the “manly virtues” of trophy hunting, trophy hunters today claim that they are conservationists (heh), and contend that they only “harvest” a “sustainable” number of lions.

And yet lions populations crashed by 43% between 1993 and 2014. In just the past 25 years alone, we may have lost half of the few remaining lions in Africa. And there’s an important reason why: in the wild, top predators regulate their own numbers. For carnivores such as lions, there is no “sustainable rate of harvest”. These are nothing more pseudo-scientific buzzwords made up by the hunting lobby to confuse the ignorant public.

In the 3.5 billion year long story of life on Earth, human beings are perhaps the only animal ever to systematically butcher healthy adult animals, usually males in their prime. All predators, including lions, primarily hunt younger animals. Adults are targeted only if they’re injured, infirm or downright unlucky – for instance, getting separated from the safety of the herd.

In 2015, a research team led by biologists Thomas Reimchen and Chris Darimont discovered that far from ensuring balance in the ecosystem, human hunters kill large carnivores 370% more often than herbivores. That’s some applause-worthy “wildlife management” right there. In fact, the rates at which humans kill predators is 9 times higher than the rate at which they’d kill each other (to protect their territories).

Human hunters kill the healthiest male predators with the best genes at a rate that’s 900% higher than natural.

By killing predators, hunters cause catastrophic damage to our ecosystems – all with legal sanction. Adult animals raise the next generation and pass on crucial life skills. And males, and especially male carnivores, have the added responsibility of maintaining social order and protecting the territory. If a male lion is hunted, for instance, dozens of younger lions in that territory may die of starvation or conflict. With one bullet, a hunter can wipe out many generations of natural predators that the ecosystem needs.

In the 1970s, Reimchen had discovered that predators overwhelmingly go after “reproductive interest” – juveniles and young that can be killed without affecting populations, whereas human hunters decimate a species’ “reproductive capital” – adults in their prime who are critical for maintaining stable populations (and cultures). The impact is far worse on top predators who, out of necessity, have evolved to sustain smaller populations.

On the African savanna for instance, an area of 50 square miles may have thousands of antelope, but barely 20 to 30 lions. In the harsh wilderness of Russia’s Far East, a vast area of 300 km2 may have barely one or two Siberian tigers. Unlike what action-packed nature documentaries show, the lives of top carnivores are anything but easy. Herbivores, having evolved alongside their predators for millions of years, are incredibly difficult to hunt. To sustain themselves, carnivores need to maintain and defend vast territories, which is why top predators are relatively rare in Nature.

If a buffalo is displaced from a patch of land, he can move on and graze somewhere else. But carnivores must defend their homelands with their very lives, if necessary. A young lion must either prepare for a lifetime of brutal conflict with other lions, or eke out an existence as a wandering nomad. And nomads don’t get to pass on their genes. As a consequence, evolution has selected male lions for dominance. An adult male lion cannot afford to show fear. When faced with a trophy hunter, their natural instinct is to stand their ground and protect their families.

“Lions don’t run away from hunters. They are not a challenge to kill.”

– Andrew Loveridge, head of WildCRU’s Trans-Kalahari predator program

Come to think of it, “human” traits like courage, self-sacrifice and a sense of fairness are really animal traits. Most humans will stand in harm’s way to protect their families, much like a male lion, a bull sperm whale, an elephant matriarch or a momma bear. We understand that it is morally reprehensible to kill a lion who just wants to be left alone, and steal his skin – just as it’s criminal to shooting a passer-by for the cash in his wallet.

Our conscience is innate and instinctive – a product of millions of years of co-existence and cooperation with other animals. Empathy and respect are neither indoctrinated through religion, nor enforced by laws; these are innate traits that we share with other animals.

In our society, as with lions, these traits can be fortified by cultural traditions, passed down the generations. And yet, cultures can also get twisted. In colonial Tanzania in the early 1930s, authorities massacred tens of thousands of antelope, zebras and buffalo in Njombe to protect livestock from rinderpest. With their natural prey gone, one local lion pride took to hunting people to feed their cubs – and became very good at it. Instead of hunting at crepuscular hours, as lions normally do, they began hunting in broad daylight, when people were easier to find, and used the cover of darkness to move from village to village to avoid retaliation. They even developed an innovative relay system to transport their victims, making them harder to track. Lionesses taught these strategies to their cubs, and between 1932 and 1947, this one small pride killed as many as 1,500 people. They had such a keen understanding of human behavior that took more than a year for experienced hunters to kill them all.

Inside the Minds of Trophy Hunters

To explain the culture of trophy hunting, I’d like to share an anecdote about their idol Ernest Hemingway (or “Papa”, as the hunting community calls him). In 1936, Munro Leaf wrote a children’s classic The Story of Ferdinand. It narrates the story of a bull named Ferdinand, who loves nothing more than sitting under his favorite tree and smelling flowers. Living in Spain, he suffers the misfortune of being sent off to a bullfighting ring.

Like all bulls, Ferdinand has no desire to fight for the perverse amusement of humans. Unlike other bulls, who would be dispatched to the slaughterhouse, Ferdinand is sent back to his flowers and tree. Leaf concludes his story thus:

“And for all I know he is sitting there still, under his favorite cork tree, smelling the flowers just quietly. He is very happy.”

Ferdinand’s story was a runaway success – Walt Disney even won an Oscar for his 1938 adaptation of the tale. Such a threat to the utilitarian world-view of hunters – a story of an animal with feelings, whose life was meaningful – could not be allowed to go unanswered.

Presumably disturbed by the success of The Story of Ferdinand, Hemingway wrote The Faithful Bull (interesting choice of words), published in 1951 …

“One time there was a bull whose name was not Ferdinand and he cared nothing for flowers … He was always ready to fight and his coat was black and shining and his eyes were clear … He fought wonderfully and everyone admired him and the man who killed him admired him the most.”

This small excerpt reveals so much about the mindset of hunters. Hemingway starts off by erasing the name of the bull, thereby denying his individuality. To a hunter, every lion, elephant, giraffe or buffalo in Africa is interchangeable with the next. On one hand, they covet specific animals – the lion with the blackest mane or the deer with the biggest antlers … but they’ll go to great lengths to deny that these creatures with unique bodies also have equally unique personalities, feelings, ambitions and memories. This is why they speak the language of numbers, not names. Hunters “take” or “harvest” animals – they never “kill” them – that would be an acknowledgement of their victim’s personhood.

“Nobody in our hunting party knew before or after the name of this lion.”

– Walter Palmer, the dentist who killed a lion who, with or without a name, had earned his place in the African wilderness

“He was always ready to fight” … Portraying the lives of animals as “nasty, brutish and short” serves the agenda of hunters. They speak of how they’re saving animals from disease and starvation. Portraying a lion as a brutal killer, a bull elephant as problem animal, or an old rhino as being useless to the gene pool, lets them mask their bloodlust as a charitable venture. All their harping about how their hunts feed starving natives is another aspect of their PR formula.

In the trophy hunter’s worldview, the bull was admired because he “fought wonderfully”, and no one admired him more than the man who murdered him. It’s in this sense that the title of the story, The Faithful Bull, is revealing. To a hunter, the animal exists only for the human (specifically, for him) and keeps the faith by letting himself be killed. It isn’t hard to draw parallels with sexism and rape culture, and notice the underlying psychopathy.

Trophy Hunting Is All About The Hunter, Not The Animal

If you disagree, just visit Google Images and search for “trophy hunting” (or click the link). Then search for “wildlife photography” – another outdoor activity involving wild animals. Next, search for “Africa safari” to see pictures of eco-tourists who, like hunters, visit Africa for short vacations.

To save you time, here are my results for “Trophy Hunting”:

This one is for “wildlife photography”:

And for “Africa safari”:

Note the contrast: in almost all photos of trophy hunting, the focus is on the hunter, not the animal. But in photos uploaded by wildlife photographers and tourists, the subject is the animals themselves. For all their talk about how they raise money for conservation, trophy hunters are an oddly self-centered lot, which probably comes as a surprise to no one.

Ending Trophy Hunting

I first started drafting this article in September 2017, while reading John Vaillant’s book ‘The Tiger: A True Story of Vengeance and Survival’, about a Siberian tiger who turned maneater after being wounded on at least four occasions by hunters. Then, the murder of Cecil was still fresh on my mind. He had been studied by dozens of naturalists, seen by thousands of tourists, and manner of his killing- and the name of the person who did it – was shared worldwide. But how many other unnamed lions, who are so important to their ecosystems and local communities, are killed in unknown ways by killers from another continent, protected by anonymity?

Many of us feel terrible about this needless loss of life. But what most of us do not recognize is that trophy hunting is an assault on our shared heritage. Wild animals belong to all of us, and we belong to them – not in the sense of property, but by ecological and emotional relationships.

Thanks to our evolutionary heritage, we find fulfillment and meaning in kinship, in beauty, and in drama. But unlike our Neolithic ancestors, we lack the privilege of living among these animals. We haven’t been taught to read, sense, or be part of the beauty, drama and kinship of Nature – and so, we crave it in our TV shows, movies and sports instead.

Much like the young lions of the Kalahari who, orphaned by hunters, knew nothing of the courteous ‘oblique walk’ that their ancestors did with native people, and thus attacked tourist cars, we too have lost the art of coexistence with large predators. Tone-deaf to the Language of the Wild, we have let trophy hunters get away with murder.

Tell Every Story

The good news is, ending trophy hunting could be very easy. After all, trophy hunters do not make their money from trophy hunting – that’s what they spend it on. When not killing lions and elephants in Africa, they are business executives, lawyers, doctors, and yes, dentists. Would they really spend all that money on bloody vacations if it meant that they might no longer remain business executives, lawyers, doctors or dentists?

The story of Cecil’s murder shone a spotlight on the shady world of trophy hunting. Already, trophy hunters are seeking anonymity to mask their deeds. In October 2015, mere weeks after Cecil’s death, a German hunter killed one of the largest tuskers in Africa during a 21-day ‘Big Five’ blood orgy. His host, SSG Safaris, went to great lengths to protect his identity. That someone would kill a ‘record’ animal and not want to be known for it, was something unimaginable even a few years ago.

The pressure must be kept up. Recently, the #MeToo movement and in particular, naming and shaming sexual predators, has precipitated a cultural shift in how we address sexual harassment. By naming trophy hunters and telling the stories of their victims, we can raise social and economic costs for them and create a strong disincentive against trophy hunting. Those among us who are storytellers – journalists, bloggers, authors, photographers, artists and filmmakers – must narrate the stories of these animals, and create the cultural change that undoes the damage of so many centuries.

Creating Wealth for Africa

Far more important is creating wealth for native communities. The vast majority of Africans have never seen a wild lion. Many of those who do, are forced into a state of conflict with them by poverty and a lack of access to technology and resources. Africans cannot focus on protecting their environment if they’re struggling to get by. How can you help?

The easiest way is by visiting Africa. Why not plan your next vacation there? If more people visit protected reserves, they become a valuable and sustained source of income for local communities. They can open small businesses – restaurants, lodging, craft-making – instead of scratching out a living by subsistence farming. And the wealthier that local communities get, the better their prospects of educating their children, adopting eco-friendly technologies, and being tourists themselves. As Africans from urban centers visit their wild areas in greater numbers, ecotourism will become an ever-growing industry, allowing more protected areas to be created, and more land be rewilded.

African safari destinations do cater to every budget. A no-frills mobile safari (guided game drives with basic tents) can cost as little as $300 per night! A vacation in Africa doesn’t have to cost much more than a visit to any other place, and your money will go directly to conservation and the local economy while giving you the experience of a lifetime.

I hope that we soon see a day when the impact of ecotourism is so far-reaching that ending trophy hunting becomes an election issue in key African countries. As African countries become wealthier, their common citizens will have greater influence over their governments’ policies, which can bring the nexus between corrupt African politicians and trophy hunting lobbies to a swift end.

The Hunting Lobby Is Not Invincible

Any social or environmental movement – climate change, anti-tobacco, civil rights, LGBT rights, women’s suffrage, or ending livestock farming – is at its core, an effort to influence public opinion and thus shape government policies. In the fight to end trophy hunting, our narrative is supported by sound science, powerful stories, and a proven model for creating prosperity.

On the other hand, the trophy hunting industry has considerable political clout and is adept at sowing the seeds of doubt by spreading misinformation – including propaganda masquerading as academic research. This is a time-tested strategy that PR firms for the tobacco, oil, dairy and gun lobbies have used with much success. And yet, the success of animal rights groups in exposing factory farming, greatly damaging the fur industry, changing animal testing practices and ending cetacean captivity shows that these lobbies are not invincible.

It is the people of Africa who have the most to lose if charismatic fauna and critically important keystone species like lions continue to be killed by trophy hunters. And it’s these common citizens who must have a financial and emotional stake in their protection from hunters. Given the tremendous influence that groups such as Safari Club have over federal and state agencies, it might be a waste of effort to directly petition them to ban the import of trophies.

But by narrating the stories of the wanton excesses of entitled trophy hunters, and the trauma they inflict for pleasure – with brutal and unflinching honesty – we may soon see a day that narcissistic, sadistic people with too much money fear the consequences of killing one of our most magnificent wild treasures.

References

-

Cohen, A. (2010) Art in the era of Alexander the Great: Paradigms of manhood and their cultural traditions, Cambridge University Press, pp. 68–69 -

Sachedina, H. T. (2008). Wildlife is our oil: Conservation, livelihoods and NGOs in the Tarangire Ecosystem, Tanzania, page 152

-

IUCN (2009). Big game hunting in West Africa: What is its contribution to conservation? West and Central African Protected Areas Program

-

Economists At Large (2013). The $200 million question: How much does trophy hunting really contribute to African communities? Final report prepared for the African Lion Coalition

-

Coss, R. G., & Moore, M. (2002). Precocious knowledge of trees as antipredator refuge in preschool children: An examination of aesthetics, attributive judgments, and relic sexual dinichism. Ecological Psychology, 14(4), 181-222.

-

Barrett, H. C. (2005). Cognitive development and the understanding of animal behavior. Origins of the social mind: Evolutionary psychology and child development, 438-467.

-

Pope Francis (2015). Encyclical letter Laudato Si' of the Holy Father Francis on care for our common home. Chapter 1, Section III. Loss of Biodiversity

-

Darimont, C. T., Fox, C. H., Bryan, H. M., & Reimchen, T. E. (2015). The unique ecology of human predators. Science, 349(6250), 858-860.

-

Zielinski, S. (2015). Modern humans have become super-predators. Smithsonian.com.

-

Carrington, D. (2016). Cecil the lion's legacy: death brings new hope for his grandcubs. The Guardian

Article History

- Published: Jan 27, 2018. Read original version.

- Updated Mar 10, 2018. Used new detail’s of Cecil’s death shared by Andrew Loveridge. Edited conclusion to share ideas about stopping Safari Club with lessons drawn from the #NeverAgain movement

Hi, the youtube link about Ndorobo stealing meat from lions is no longer working. I found this working link which you might want to use instead: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QDubMeNlSxc

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! It’s so very kind of you to let me know! I will update the link in the article. In light of some recent events and new studies, I also have further updates planned for this post. Thanks again!

LikeLike